Move it, move it: how physical activity at school helps the mind (as well as the body)

from www.shutterstock.com

Brendon Hyndman, Charles Sturt University

Federal Sports Minister Bridget McKenzie recently unveiled plans to convince state education and sports ministers to ensure sport and physical education is compulsory in schools.

The physical benefits of getting kids moving have been well recognised to help prevent chronic disease and develop movement habits across their lifespan.

Read more:

The rise of the Fitbit kids: a good move or a step too far?

Yet one of McKenzie’s key points, to push for mandatory physical education, was based on improving school results.

This statement is an important and positive shift in the education sector. Until recently, bodies and minds were often considered separate entities when it came to education.

Physical education has been perceived as only dealing with the “movement of the body” or the “non-thinking thing”. So historically, it has been pushed to the periphery. For example, physical education is yet to be an endorsed focus for the national senior secondary curriculum.

Yet over the past two decades, growing research has strongly recognised the inter-connections between body and mind.

How can movement help a student’s brain?

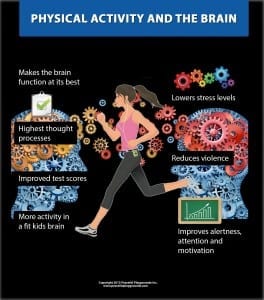

Brain processing takes up about 20% of our total metabolism through cognitive activities like memory, attention and concentration.

This cognition needs a strong flow of fuel (glucose, oxygen) and hormones to activate and enhance the brain’s capacity to perform, learn and get rid of waste.

So any prolonged sitting and inactivity can lead to negative cognitive consequences. For instance, inactivity in childhood has been linked to reduced working memory, attention and learning.

A student’s brain does not keep itself healthy independently. It is the connection with a healthy, moving body that can help improve brain performance.

Physical activity is also important in developing students’ brain structures (cells/neurons) and functioning at an early age.

The human brain is not fully developed until the third decade of life, so getting kids moving can be a powerful academic strategy.

What does the research tell us?

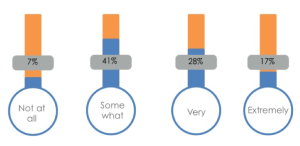

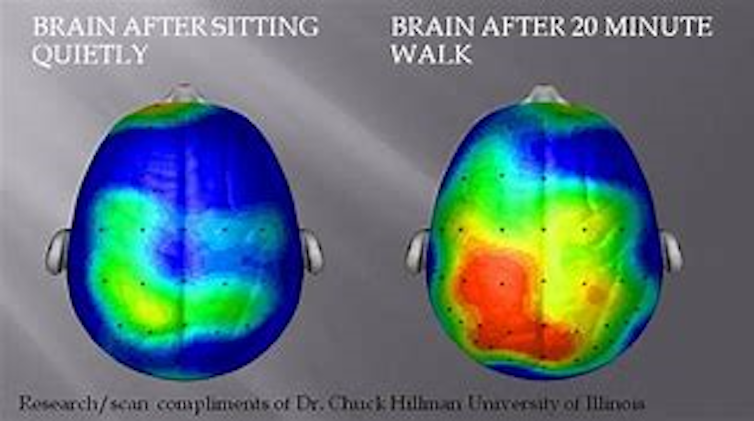

More studies are linking physical activity and improved cognitive function. One of the most globally recognised found primary school students’ level of cognitive function increased from just 20 minutes of walking. Students did better in an academic test and had improved attention.

Author provided

Since this study, there have been many other US studies that have established links between physical activity and students’ academic performance, including from the north east (with more than 1800 students) and Texas (2.5 million students).

Several large scale reviews have also identified links between physical activity and students’ academic performance, for example, grades and test scores.

In Australia, a study of 757 primary school students across 29 primary schools found fitter children had higher NAPLAN scores. Students with specialist physical education teachers also had higher numeracy and literacy scores.

Read more:

From grassroots to gold: the role of school sport in Olympic success

There is also evidence of improved cognitive performance (attention, memory, concentration), self-esteem, mental health (reduced depression, anxiety, stress), enjoyment and lesson engagement from school students’ participation in physical activity.

What type of physical activity is best?

Researchers are still working out what types, conditions and length of physical activities can have the most effect.

For instance, going for a routine walk requires less decision-making and intensity than completing a Tough Mudder or Ninja Warrior course.

Read more:

Why we should put yoga in the Australian school curriculum

Top 5 tips to provide high quality physical activity at school

1. Curriculum

Opportunities to take part in authentic (resembling real-world) games and sports, embedded with reflective and guided thinking opportunities. This can help students develop solutions to movement problems and understand sporting traditions, roles, teamwork and rules.

2. Classroom

Provide active breaks (short break of a few minutes) with simple and/or integrated physical activities like moving to music during prolonged, inactive lessons to improve academic engagement.

3. Recess

Access to a larger variety of mobile equipment can engage students in more creative exploration of physical activities.

Mobile equipment can encourage more variety and choice for students to design complex, evolving physical activities beyond fixed locations.

4. Before and after school

Partnering with national sporting organisations through programs such as Australia’s Sporting Schools.

Students can then pursue sports and physical activity beyond those facilitated at school and by the program.

5. Active transport

![]()

Set up a walking school bus or bicycle train to plan a safely structured walk or ride to school with one or more adults, depending on air quality, distances to school and busyness of streets.

Brendon Hyndman, Senior Lecturer and Course Director of Postgraduate Studies in Education, Charles Sturt University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.